June 22, 2021

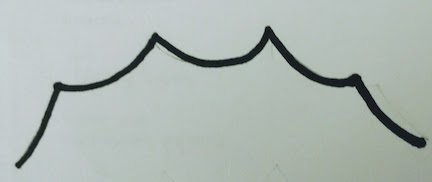

My sister and I lived in a tent for a year as children. It was a big, heavy, green canvas thing. Folded it weighed about sixty pounds. On the interior were poles to help it stand—sort of like columns in a grand house, if you have a generous imagination. In the upright position it sort of looked like a capital letter M raised in the middle and squished down on the sides. Like this:

In the sixth grade I was, for the first time, one of the shortest kids in class—if not the shortest. Little did I know this distinction would last through the tenth grade. At least the height allowed me to stand up without bending in the middle of our tent. My sister didn’t have that luxury.

As a teenage girl coming into her own toward the end of 9th grade she probably wasn’t as happy as I was about this Tom Sawyer-like adventure. Nevertheless, we managed to coexist—me on the right side and she on the left. She may have had a moment where she felt like she needed to clarify the demarkation, but the devision was pretty clear given the rectangular footprint and the egress flap in the middle.

The history of how we ended up living in the tent goes like this:

We were in the ramshackle farm house. My parents (while working full time jobs) were intent on getting back to the land as so many young people of their generation were. Rodale’s Organic Gardening and The Whole Earth Catalog were popular publications around my house. The farm had been a small, working dairy in its day. The old house, with sagging and uneven floors, sat on 14-acres of land with three barns including the low-ceilinged milk barn with it’s rough concrete floor and feeding trough and seven iron head clamps for the cows. They bought a Red Jersey milk cow which I had the pleasure of naming Fern after the book my fifth grade teacher, Mrs. Ann Hall, was reading us: Where the Red Fern Grows. We had a quarter horse named Sugar, laying hens and two calves bound for slaughter when they became steer. Fern had birthed Bo and we bought a black Angus to join the suckling. Triangle was named for the white mark on his forehead.

My parents planted an impressive quarter-acre garden with bountiful crops of beans, tomatoes, okra, and potatoes to name a few. The year and a half or so spent on the farm was an intense time of real and metaphorical fruition. My parents had a knack for this life for sure, but given the demands of their regular jobs it wasn’t likely they could keep milking a cow twice a day forever, not to mention keep up with all the other tasks of a working farm. Besides, change and adventure seemed to be their greatest love.

My fifth grade friend and classmate, Donald, told me that his family was moving back to California and that their Texas ranch house was coming up for rent. His dad was an airline pilot for American Airlines. He may have been doing training out of the new Dallas International Airport. They could well afford the rental on a house that was actually a modern mansion.

I told my parents that we should move into it. Mom and Dad had already been apprised of its wonders by a few visits I’d had to Donald’s. I was surprised when they thought about and enthusiastically agreed.

The house sat in a valley down a half-mile long dirt driveway off Teasley Lane a mile or so past a neighborhood of affluent homes. It was where Teasley changed from a main neighborhood feeder vein for south side of Denton into a rural highway. It’s where country began again.

The half-mile long, dirt drive leading to the property ended at a pad of perfectly smooth white concrete that wrapped around to a three-car garage. The mansion was an all-electric wonder with wall to wall powder-blue shag carpeting, central vacuuming with hoses that plugged into the wall, five bedrooms, a thousand square foot living room with anteroom, five bathrooms each with silent-flush toilets, a swimming pool, a grand patio with an eight foot circular fountain and an immaculately clipped pure green lawn that spanned the homes long front and curved around to the pool. So perfect was that carpet of green that it must have contained enough glyphosate to evaporate any weed seed floating through the air even before it landed.

This manufactured eden sat like an island in the middle of a vast acreage of fenced off grasslands which rippled with the wind and measured time in the shadow of clouds drifting across it. Hundreds of acres spanned the North and South and to the West there was a lake stocked with bluegill, bass and crappie. A back pond on the East side contained catfish and water moccasin. The pond sat in a basin just before the land sloped up to a thin forest behind which sat, hidden from view, a state school where severely mentally disabled people were institutionalized.

Little sound, except that made by nature, made it to this island. From the lake at the front of the property you could hear thirsty engine manifolds sucking air as drivers put a heavy foot to the floor speeding away from suburbia. For a viewer, a car’s forward momentum could look like a mirage in the distance. It might seem as if a land rocket was making ground, pulsing unevenly, through curtains of warm air.

This is all the long way around to saying that my parents, for the experience of living in Shangri-La, blew all their money. The electric bill alone was $300/month. That’s 1976 dollars. Along with the rent, it was way beyond their means. Dad also bought a used, but almost new, Cadillac to balance the picture of him as a wealthy oil tycoon or cattleman.

I’m not sure what blew all their money meant—whether they used up all their savings or went into debt—but their solution to get back on track was to buy a 19-foot-long pull trailer, find a place to haul it and stick us alongside the camper in a tent.

That’s the condensed version of how we ended up in a tent—first at the Shady Oaks Ranch followed six months later by the Denton K.O.A.