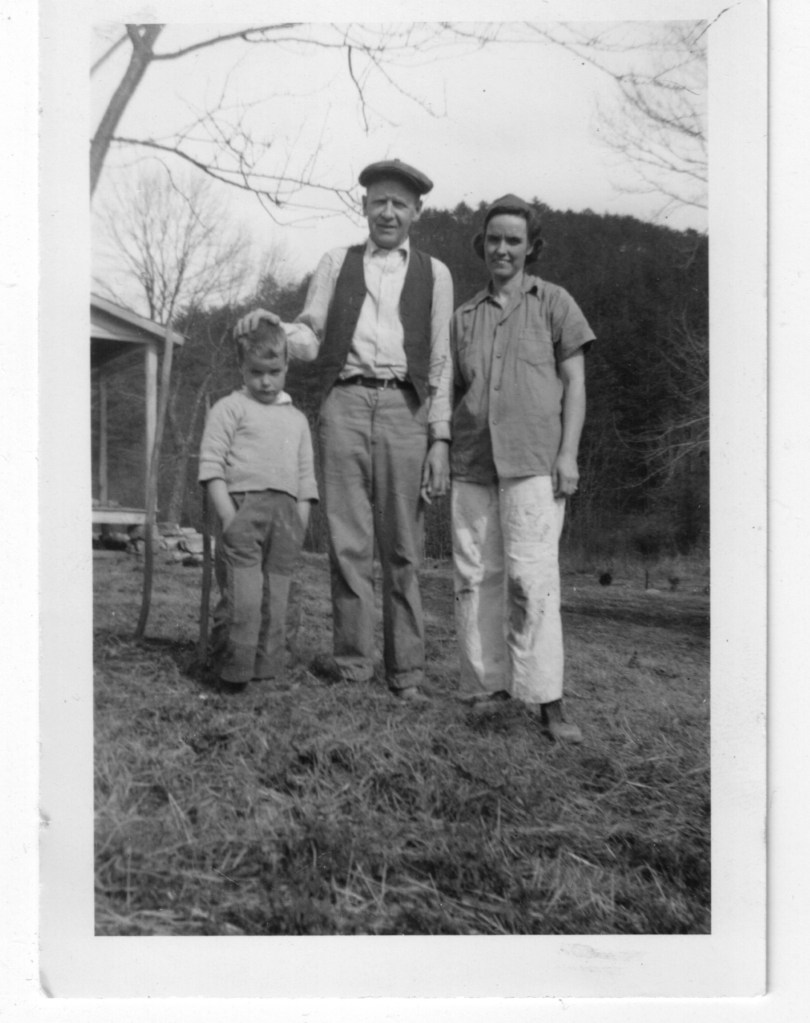

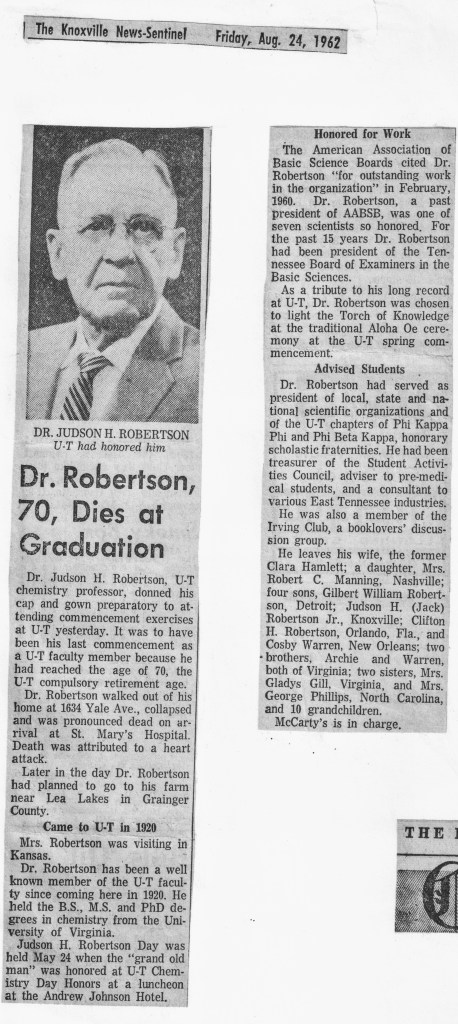

I feel very lucky to have land I can dream about going to. I did nothing to earn it. This land was walked on, dug in, slithered across and flown over for millions of years before I existed. It comes to me through the ambitions of my grandfather, a long-time chemistry professor and head of the department at the University of Tennessee. He was likely able to acquire the land at a good price during the great depression. Other people’s hardships worked in his favor.

Before him the land was taken from the original people through occupation, trickery and force by the mass of European-Americans who arrived to this “new world” which was for everyone else very, very old.

According to a neighbor there is the largest black bear he has seen that calls the “cute triangle” part of his territory and I would do nothing to take it from him.

We are all occupiers on some level and it seems to me it is best to learn to share. What we do on land does not stop at fences. Clear cut forests erode neighboring lands and choke rivers. Oil extraction pollutes ground water. Non-native species can destroy habitats. Relocating people, not to mention killing them, creates societal disharmony for many generations to come. Such was the case for the Cherokee who resided here before the European-Americans.

——————–

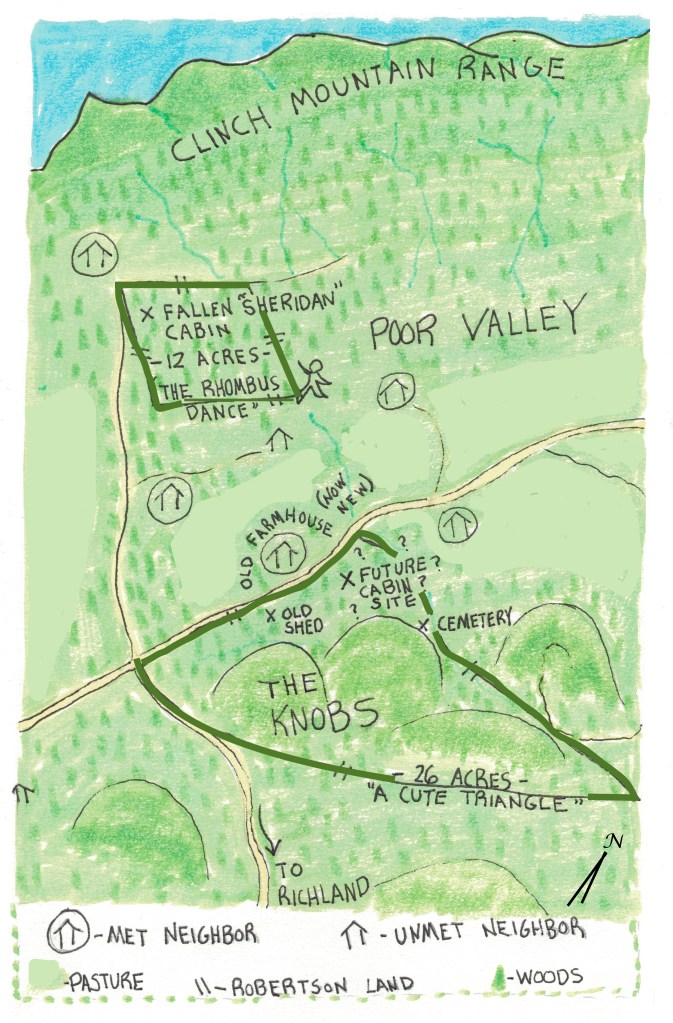

It is not a metaphor to say I couldn’t see the forest for the trees this past summer. The only boundary I knew was the one that ran along Poor Valley Road. The green briar, poison ivy, downed trees, saplings, vine and bramble made walking through the forest a chore. To avoid a face full of spider webs I had to carry a stick and wave it about like Harry Potter continually casting spells.

My one attempt to start to discover where the boundaries lay was given up after ten minutes of crawling over downed trees, scrambling under overhanging branches, and trying to shake off vines that grabbed my legs like monster tenacles trying to pull me to center earth.

Winter is a better time to walk untended land. The overgrowth is died back. On my recent trip all the leaves had dropped except for the beech saplings whose leaves seemed to hover like drifting copper fog.

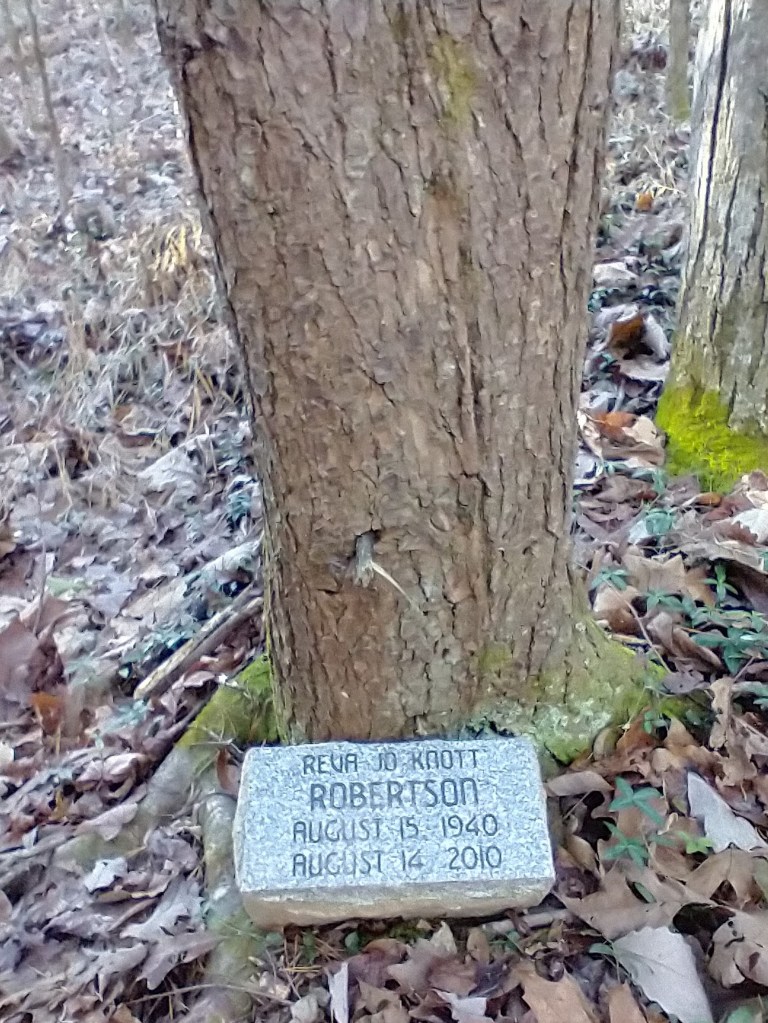

The forest was mostly brown. Splashes of green came from lichen and moss on tree trunks and higher up, the needles of various evergreens – loblolly, Virginia and white pine, cedar and around the memorials, hemlock.

More green lived around the memorial stones, in the form of Vinca minor, also known as cemetery plant. It was seeded by my grandmother Robbie three decades ago.

Seemingly absent, but just hiding in dormancy, was the sea of poison ivy that predominates during the summer. There was Christmas fern and a plant with dark green leaves with white stripes called pipsissiwa—a fun word to say.

I learned these plant names from Jeff, the forester I hired to tell me about the land and what was growing on it. I hardly knew where to start when I met him at 8:30 the morning of December 20. The wonders of the internet meant that all I had to do was give him the address of the nearest neighbor.

Back in the 1970s when I first visited this land with my family, my father had a hard time finding it. He’d probably not been back since his father’s burial in 1962. On subsequent trips, every decade or so, it was the same thing. He’d squeeze his eyes peering out the dusty front windshield, mouth agape, then mumbling, now where is that road? It was like the place he’d known intimately as a child and teenager had disappeared with the death and dispersal of his family.

Going to it makes me feel like I’m resurrecting something that my father was unable to. By the time he introduced me to this place it may have only contained ghosts of what seemed to be a dream-like childhood obliterated by reality. It may be why he went into the theatre—so he could always have fresh dreams.

This was the first winter I’ve ever been to this place. It was not until I was traipsing through the forest with Jeff that my worries were eased about how he would identify trees without leaves. The bark and branching patterns were enough for him. It’s a bit like birders who use wing flap and silhouette to identify species without relying on color patterns or call. Yellow poplar, commonly known as tulip tree is abundant on the property. Jeff showed me how to identify it by the seed pods that hold on high in the limbs. Fortunately tulip poplar is a good wood if I decide I want to mill my own lumber for a cabin.

After watching numerous YouTube videos, I’ve decided I don’t want a log cabin but would rather have a stick or timber frame. Stick frame refers to the most common building method used today with lots of 2x4s. Timber framing uses fewer but more substantial pieces of lumber like 8x8s.

Other species identified on the land include four or five types of oak, red maple, hickory, dogwood, eastern red cedar, and gum.

The largest tree we found was a 42-inch white pine not far from the old shed.

Beyond the lesson of tree and plant species Jeff gave me an introduction to compass reading. I have a long way to go before I figure it out. The survey maps I have give compass readings from established points on the boundary. While I didn’t learn enough to use those I took a closer look at markers on the map and was able to use a downed barbed wire fence to establish a close approximation of the boundary line for the longest side of the cute triangle. Elevation maps also helped me estimate boundaries as well as another tip from Jeff about how to use a consistent stride to measure distance—something that is easier done when the winter die-back doesn’t require as much vertical leg movement.

I want to take my time getting to know this land. It seems like a large percentage of the harm and waste of resources that we encounter in the world has to do with our rush to get things done.

Jillian is a big fan of British narrowboats—a pretty slow, but relaxing way to get around. Yesterday morning she turned me on to the Falkirk Wheel. This is an amazingly engineered lock that can lift 600 tons of barge and water eighty feet in the air using roughly the same amount of energy it takes to boil eight tea kettles of water. It takes five and a half minutes. Five and a half minutes is like sitting through three or four red lights—something that feels interminable trapped inside a car but a whole different thing if you are being lifted heavenward in a boat.

It’s easier to go slow when you affirm that it’s all about the trip, not the destination.

——————-

One last thing…if you look at the “about” section of my blogsite I’ve said “A journal of nature, race and place.” That’s a pretty grand statement and I don’t know how true I will stay to it. My original summer journal had a clear directive to find all the places I’d lived growing up. Travelling back to those places I realized how intertwined they were with our American notions of race. Talking about my experience with race is a big interest to me and it feels somewhat safe here where I can control the narrative and choose who it goes out to. Perhaps it is an indication of the unsteadiness I feel that I have set these parameters, but confronting issues around race is something I deal with on a daily basis as a public school teacher on a campus with such a wide variety of children from multiple backgrounds.

Rarely are the issues directly about race although sometimes they are, like when I had a discussion with two students who together decided to tease a child by equating racial identity with a sport. I’ve often had to talk to children about making fun of how someone speaks. I suppose this is more about nationality than race.

Mostly I deal with the legacy of racism which involves issues of poverty, privilege, and long-standing hurt. One of my favorite things to do with a kidney-shaped table full of newcomers is to look into their Yemeni, Guatemalan, Salvadorian, etc., eyes and sing “This Land is Your Land” pointing back to them with each “your” and back to myself with each “my”. Six-year-olds know what it is to feel like the land is not theirs and I like to disrupt the narrative that makes them feel this.

Next up: More cabin and land plans. A continued exploration of the history?