Happy New Year friends. I’m just back from a visit to see family in Tennessee and meet with a forester I hired to walk with me on the land I became enthralled with while writing my summer travelogue.

If you are seeing this for the first time and wondering what travelogue? Let me explain: In June, I left California with an outfitted camper on my truck with the intention of visiting and writing about every place I lived with my family growing up. The result is a 43,000-word journal which I will send in a separate email at your request. The pictures have lost a lot of quality in its current, compressed PDF form, but the writing is intact if you’d like some cozy winter reading.

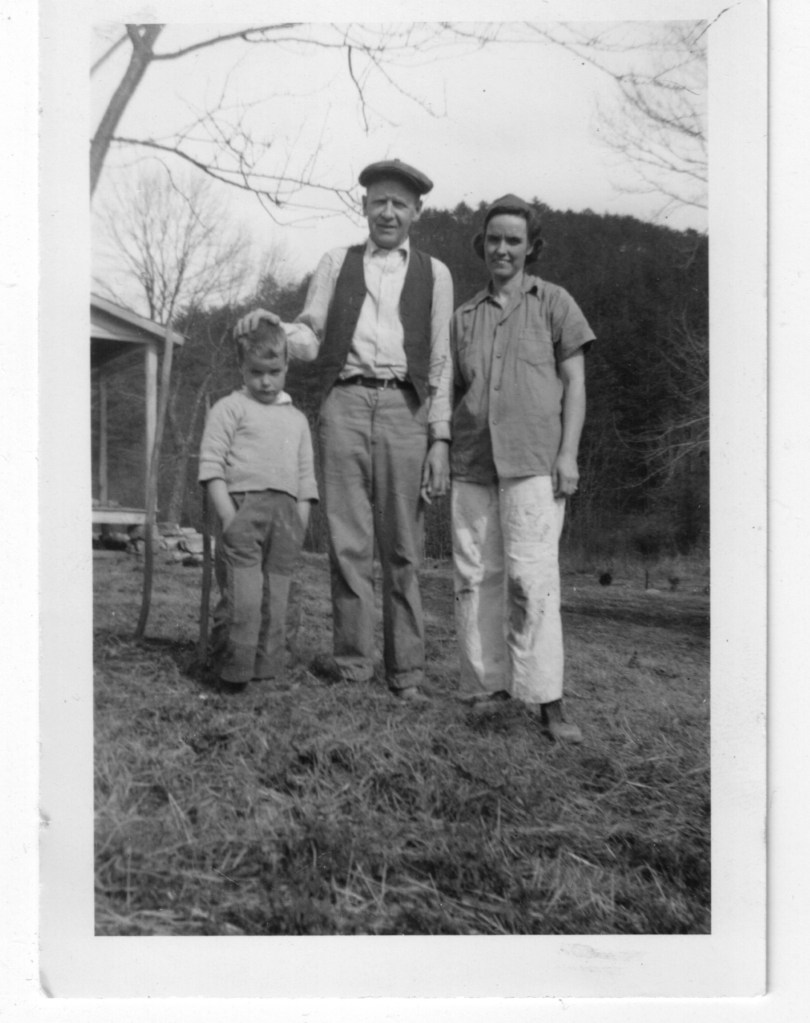

The land was not one of the places I lived, but has much family lore associated with it. Just 23 miles northeast of Knoxville, it was acquired by my grandfather starting in the early 1930s. For the next decade he continued to buy contiguous pieces until there were over 100 acres. I’ve been looking through old photos taken before I was born and comparing them with photos I took this past summer.

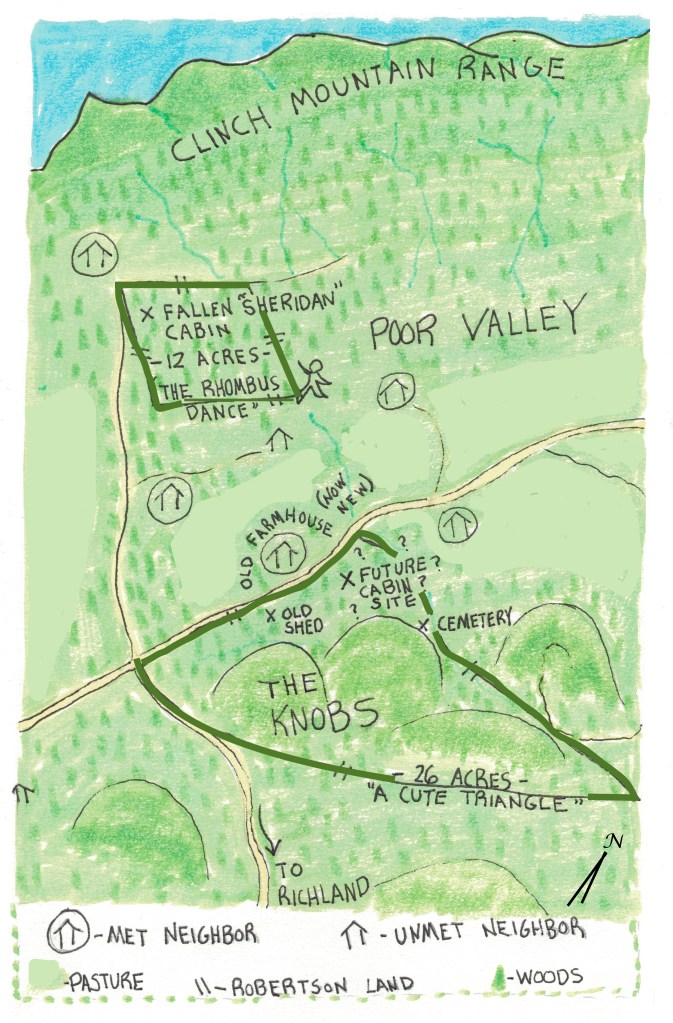

This road dissected the original piece. The farm house is visible in the old photo. Now the family property only includes what is on the south side of the road and a piece north of the road but not touching. Both are heavily wooded areas.

My grandfather Judson was a University of Tennessee chemistry professor. He bought the land and farmhouse as a place for his family to spend weekends, holidays and long summers playing, farming and exploring the woods. His plan was to eventually retire there.

My father, born in 1937 and the youngest in his family, had many memories associated with this place. Some of his stories include being snowed in and carried out on his father’s back to go get help for everyone left behind, getting buzzed by his half-brother Gilbert flying low over the farm during training to be a WWII pilot, and breaking his leg in a homemade box car ridden down one of the hills with his brother Clifton.

Dad, circa 1955, leaning on the same mailbox I pulled out of the shed this summer.

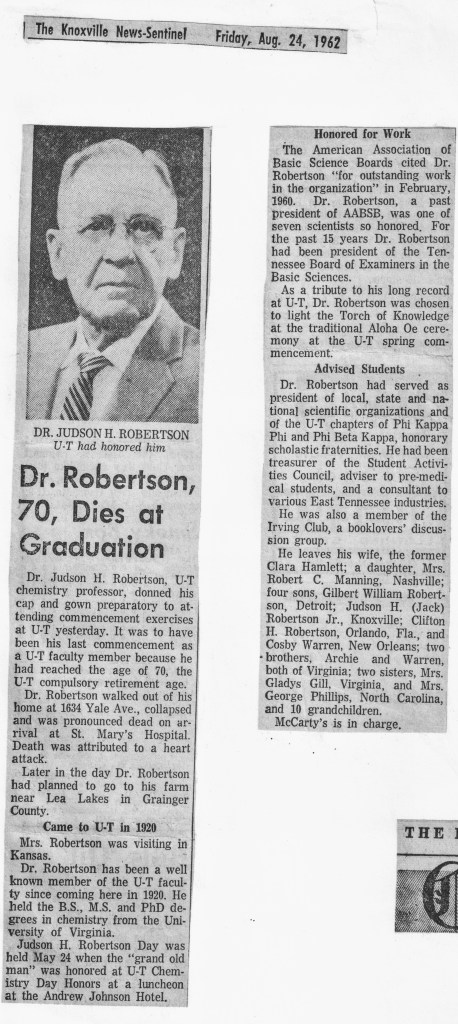

My father had not been long out of the nest when after 42 years at UT my grandfather died in his doctoral cap and gown at what was to be his last graduation ceremony before retirement. I never met him. (A rather astonishing photo shows the exact moment of the heart attack and the pained expression on his face.) My young parents had just left from a visit and were on their way back home to New Orleans where dad was attending Tulane. Mom was six months pregnant with my sister. They were stopped by a state trooper in Louisiana and told they needed to call home.

My grandmother Clara started selling pieces of the original acreage in the 1970s. The old farmhouse and sections of cleared, farmable land were the first to go. What remained was divvied between interested children. Today what is left in my family is a 26-acre section with borders in the shape of an acute triangle and a 12-acre piece in the shape of a rhombus. The two do not touch. The triangular piece is where my grandfather is buried and also where I might like to build a cabin.

The rhombus sits closer to the base of Clinch Mountain, first ascended by some Paleo-American predecessor to the Cherokee, but credited to Daniel Boone and William Bean in European-American history. The ascension may not be noteworthy as a purely physical accomplishment. The 150-mile mountain range is 4,600 feet at its highest but just over 2,000 feet near the land deeded to me and perhaps human/animal trails were already in place. However, the Clinch range along with higher Appalachian mountains mark western expansion of European-Americans into territory previously unknown to them.

From a wooded access road the 12-acre piece drops away gradually and then dips into a slanted bowl. Overall, the elevation changes are less extreme than the triangular piece which is further from the mountain base and characterized by several high knobs. The rhombus is also more open with large hardwood trees and less green briar and saplings. A few rather dramatic boulders of both the spherical and chunky type are lodged in the thawed, winter loam. One looks like it would make a nice picnic table. I imagine these boulders coming loose from the mountain top eons ago and thundering down the steep side snapping trees and throwing up wedges of earth until reaching their final resting place. I like the feeling of permanence these big rocks engender. I don’t like the idea of anyone moving them.

The Sheridan cabin, two-rooms with a metal roof sits near the south west corner. One room has collapsed and much of the walls of the other are open. I intend to salvage the roof of the fallen section and take it to the other property where I have my sites set on a flat shelf that juts out from the tallest knob. It is here I’d like to build a cabin that overlooks the little valley between the knobs and the mountain on the other side. Both pictures above were taken this year—the first in summer and the other in winter. The summer shot is on the uphill side and the winter on the downhill side. Note the visibility afforded during winter time. The time to walk land, find boundaries and plan is after leaf fall.

Incidentally, the land between the knobs and Clinch Mountain is called Poor Valley. My father talked about how this land wasn’t much good for farming. On the other side of the knobs, closer to the Holston River is Richland which is superior for growing food. I mentioned the poor soil to Jeff, the forester, owning the same lamentation that my father seemed fond of, but Jeff had a different take.

“What isn’t good for vegetables isn’t necessarily bad for trees,” he said. “It’s all dependent on what you are growing.”

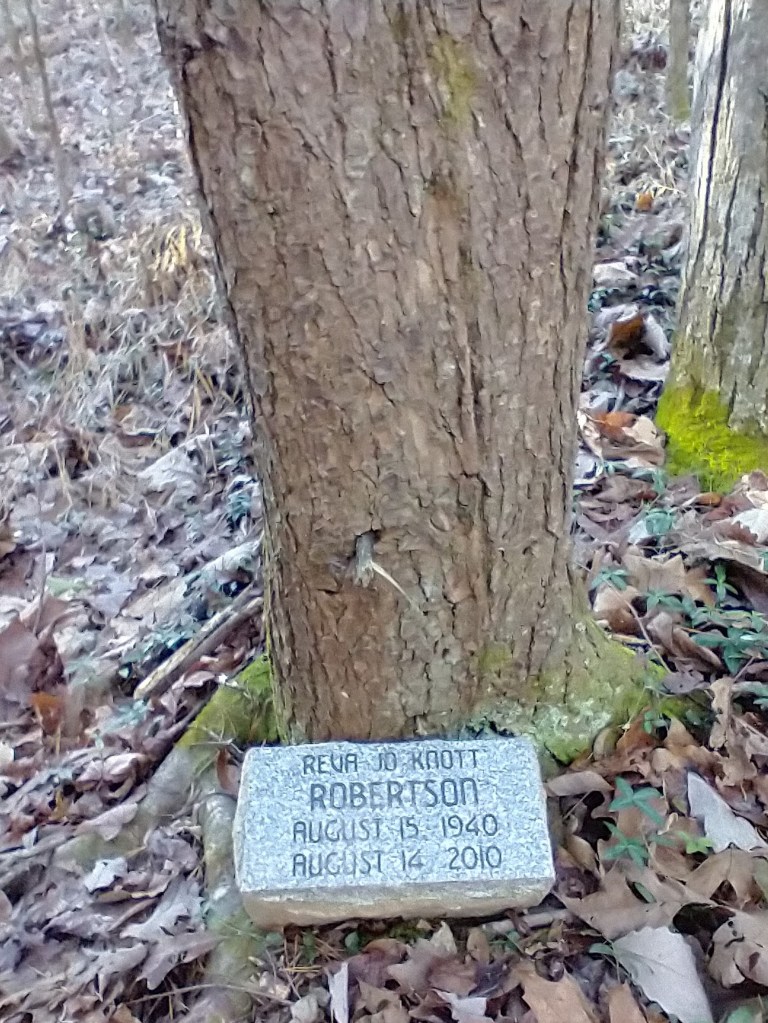

The shelf that extends out facing the mountain–the place where I’d like to build a cabin–begins to tilt around one side of the knob where the family cemetery is about 50 yards away. Three seven-foot granite slabs make up this small family plot at the base of the two-hundred foot knob. During this trip I added a marker for my mother. My parents had been divorced for 20 years at the end of their lives, but I don’t think mom would mind being memorialized alongside her in-laws.

I placed my mother’s memorial stone at the base of a double hemlock. Mom’s favorite tree was a Weeping Willow. There are none of those on the property. Hemlocks are a little weepy though so maybe that’s good enough. Eventually I may plant a Willow tree.

Although these recent photos make the woods look pretty tidy the summer foliage is gone and overgrowth died back during winter. Saplings abound and if I’d had more time I would have pulled a bunch from the wet soil while it was easy to—primarily along possible walking paths. Unlike the old photo you see below, the cemetery area has been left to go wild for many years now. I’m not necessarily a nice-and-neat lawn type person, but this land could definitely use some pruning. I’d like to make walking paths throughout with stopping spots for—as the forester suggests—places to take tea.

On the opposite side of the knob the shelf slopes downward in a sort of ramp and near its lowest point next to a gully sits an old shed.

This is the same shed I spent many days cleaning out this past summer. Among other things it contained dishes, clothes, shoes, books, photos and memorabilia, skis, bat boxes, whisky stashes, tools, hardware, and games, most in their final stages of deterioration. Extra mattresses and old army bed frames were kept there during its heyday to be pulled out for guests at the farm house. Much of the mattress batting had been relocated by mice to make a well-constructed miceopolis that has grown up this past half century while humans stayed afield.

The bat boxes were sort of mouse high rises filled with the soft cotton. Three wooden chests were apartment complexes. The high and low shed shelves had corners filled with mouse material making me wonder if mice real-estate values are based on elevation and view just like humans’. There was chewed up paper and batting in shoes and I imagine the mice had fairy tales about the old mouse who lived in a shoe and had so many children she didn’t know what to do—except being a mouse she knew exactly what to do and likely moved up to one of those deluxe apartments pretty quickly with that kind of progeny.

Three blind mice is the worst sort of horror story here except for me who—in a matter of days—came and destroyed the years of work by these Lilliputian-like beings. I’ll never forget the tender eyes of one that came out from the soft fluff inside a wooden crate, looked at me, and then dove over the side before I started cleaning it out.

Next up…my walk in the woods with the forester.