Two Italian-American companies are putting in new sidewalks on my street. Sposeto is doing the sidewalks. Ghilotti is doing the accompanying roads. Taken together the names make me feel like I’ve walked into an Italian creamery. The job they are doing is sweet. The sidewalks have beautiful lines and are clean like a newly frosted cake. The project is moving along quickly. The whole neighborhood is smiles as we see our tax dollars at work.

Concord is a town in what is increasingly less of an outskirt of the central Bay Area. But it is on the edge of country and I often relish the knowledge that I can drive west of here and quickly be in an area that feels like amber waves of grain. If you walk around my neighborhood you occasionally come across a fenced in yard that upon further inspection is really more like a field. At the back of one nearby is an old metal windmill rising up between patches of prickly pear cactus.

My street is half of a large oval. It starts and stops on the same street it curves off of. It’s what’s left of an old horse race track that existed in the late eighteen and early 1900s. The green park around the corner where I take Sasha for walks was the centerfield where the winning horses were given their ribbons and where fans sat around picnic baskets to watch the race.

The margins of the street were all gravel until this new sidewalk started to appear. All told, a peek into a backyard field strewn with piles of junk and blackberry bramble could give a deceptively country feel. But walking in most directions you will find that soon enough the squabbling of scrub jays and mockingbirds is replaced by a yawling white noise as you reach one of the main thoroughfares that flow cars like red blood cells through an artery.

A good portion of the 125,000 residents that live here are commuting in the direction of Oakland and San Francisco. The ones that don’t get there by BART train are doing it in their cars.

Recently I’ve started walking Sasha in different directions to try to accustom her to the sights and smells that surround us in case she ever gets loose. She is skittish around loud noises so it’s hard to walk her along one of the busy roads but I hope that she will build up some tolerance. I’d hate for her to run hairy scary into traffic for being too freaked out.

On our walks I have her sit at cross streets and wait with me to look both ways before we cross. I’m not sure if she’d do that on her own but I want her to know that where a road crosses you have to be extra careful.

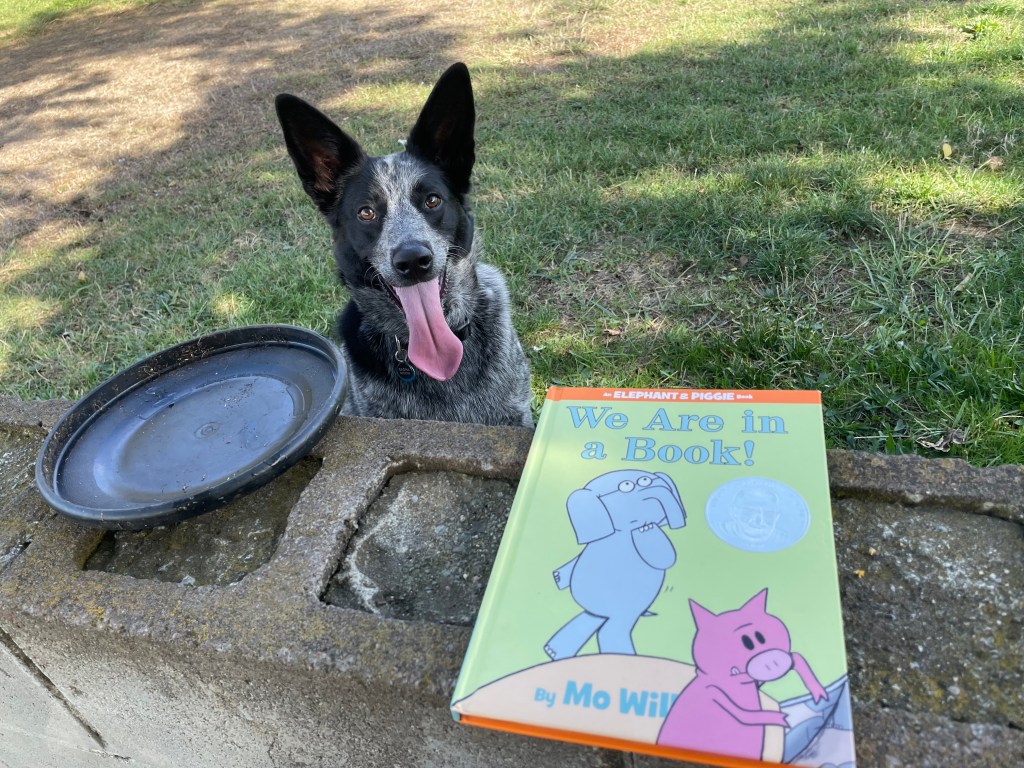

On a recent walk Sasha and I stopped by a Little Free Library nearby and found a copy of Mo Willems’ We Are in A Book. I almost never find used copies of his books much less free ones. This title along with Should I Share My Ice Cream is probably the most popular of his twenty something titles.

We Are in A Book is funny and profound. It gets you thinking about mortality and what it means to exist. For several of my last years teaching in Oakland another first grade teacher, Ms. Sandoval, and I would act out one of these two books at the school’s annual Family Literacy Night. It was always a hit and we’d have a fifteen minute show within each of the three thirty minute rotations. Several times we got donations of Mo Willems books to hand out. It was so fun! After doing this for a few years we had it down and could get the show up and running with only one or two rehearsals. Ah, the excitement of live theatre!

——————-

I want to tell you about another fantastic book I recently finished. It was recommended by my old friend Elijah. It’s about the Mississippi city he grew up in and where I went to school from 8th grade through my first year and a half of college. It’s called Hattiesburg, an American City in Black and White.

There is certainly something extra special about reading the story of a place where you walked and grew, but this book is also extraordinary because of the way that the author, UNC history professor, William Sturkey, shows the power and framework of Jim Crow.

Sturkey is particularly effective because he manages to resist any discernible ax grinding despite having black ancestry. He lets history itself be the flat stone that makes indisputable facts sharp and painfully apparent.

The book helped me understand better how a boy like myself raised in a liberal, artsy, educated household could not be immune from racist beliefs. It helped me understand how Hollywood may have got it right spiritually and mentally (if not physically) when they sometimes showed southern black communities with white picket fences and children dressed in clean, starched and pressed clothes. And it helped me understand the depth of a brutal social construct that I always felt as a coiled threat beneath the gentle surface of southern hospitality.

Without trying to explain what I mean by all those statements, I want you to know that Hattiesburg is both horrible and hope-filled as it looks at the resilience and determination of black people in a Jim Crow southern town. These are the people that went to Washington to try to get their right to vote enforced. It explains some of the humored looks I got from a few elders when I stepped into the black neighborhood that started across the railroad tracks behind my house, a naive but sincere 18-year-old trying to register voters to support the Mondale/Ferraro ticket in 1983. I had no idea who I was talking to.

It was also fascinating to make a connection with a previous book that I’ve recommended: “Ecology of a Cracker Childhood” which bemoaned the loss of old growth Long Leaf Pine forests throughout the south. It turns out that Hattiesburg was founded and built as the hub of a vast network of lumber mills cutting down those forests. The mills ran continuously for fifty years bringing prosperity to hundreds of thousands of people from the 1880s up through the Great Depression until the last of those great, majestic pines were cut down just like the fictional Truffula trees in Dr. Seuss’ story The Lorax.

Hattiesburg, the book, also ended any misconceptions I had of white Mississippians who tried to wear the banner of proud, self-determined, state-rightist who remained independent of outside influences they thought would sully their whiteness.

The town was established post slavery and grew quickly because of the help and investment of northern industrialists and the mass of low-wage workers. After cutting down all the trees it survived the Great Depression, holding on by its fingernails with federal relief and recovery funds. Then leading up to WW2 Hattiesburg was renewed as an economic hub with the federal renovation and expansion of Camp Shelby which housed and trained up to 40,000 soldiers at a time.

Throughout this era blacks took the lowest wage jobs available to them and during the depression only received federal and NGO relief when it somehow made it past the hands of local authorities who made sure whites got more than their share.

Eye-opening indeed was the extent to which white southerners held a burning cross in one hand fighting off what they saw as federal encroachment while using the other hand to collect federal funds. Socialist-minded Franklin Roosevelt got well over 90% of the Mississippi vote in all four of his presidential elections…and almost all of those voters were white because of exlusory voter registration practices.

In Hattiesburg the racist registrar of voters regularly used the question, “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap,” to exclude blacks who needed something harder than the state constitutional law questions or reading tests required to gain their voting rights.

The unexpected story is the community pride and the black town that grew up next to the white town with its own set of businesses and its own set of leaders. The unexpected story is the way people not only survived but thrived. Even for those who moved away they remained connected to Hattiesburg. Chicago may have been the most popular destination. The latest issues of The Chicago Defender newspaper were regularly passed around until they were worn out and news stories about Hattiesburg regularly made it into those Northern black-owned and operated papers.

Anyway, there is so much more to say about this book but it is better read.

—————

Before I go, I want to show a few things that I left out of my last blog post concerning work on my Tennessee land way back at the beginning of July. (I’ve really missed getting a post out sooner.)

These are the steps I put in to help make the walk easier up the small hill on the main trail that leads to the proposed cabin site. This work is what had me battling the horse fly. (Yes it was usually just one at a time but that was enough.)